When it comes to making an environmentally conscious choice for your next vehicle, people are betting electric is the way to go. But are EVs really as green as they claim? A quiet, zippy electric car sure seems easier on the atmosphere than a gigantic gas guzzler. But what are the hidden environmental costs of production? How did that car get on the road in the first place?

EV's Dirty Secret

Manufacturing takes an incredible toll on the environment and releases tons of greenhouse gas emissions every year. Making cars is no exception. The manufacture of electric vehicles produces more carbon emissions than conventional cars, according to a 2020 Congressional Research Service report. This comes down to the effects of mining, transporting and refining battery materials.

But EVs do “break even” with gas powered cars over time. How long does it take to reach that point? Does it matter where you live and how you power your car? How much does electricity generation matter?

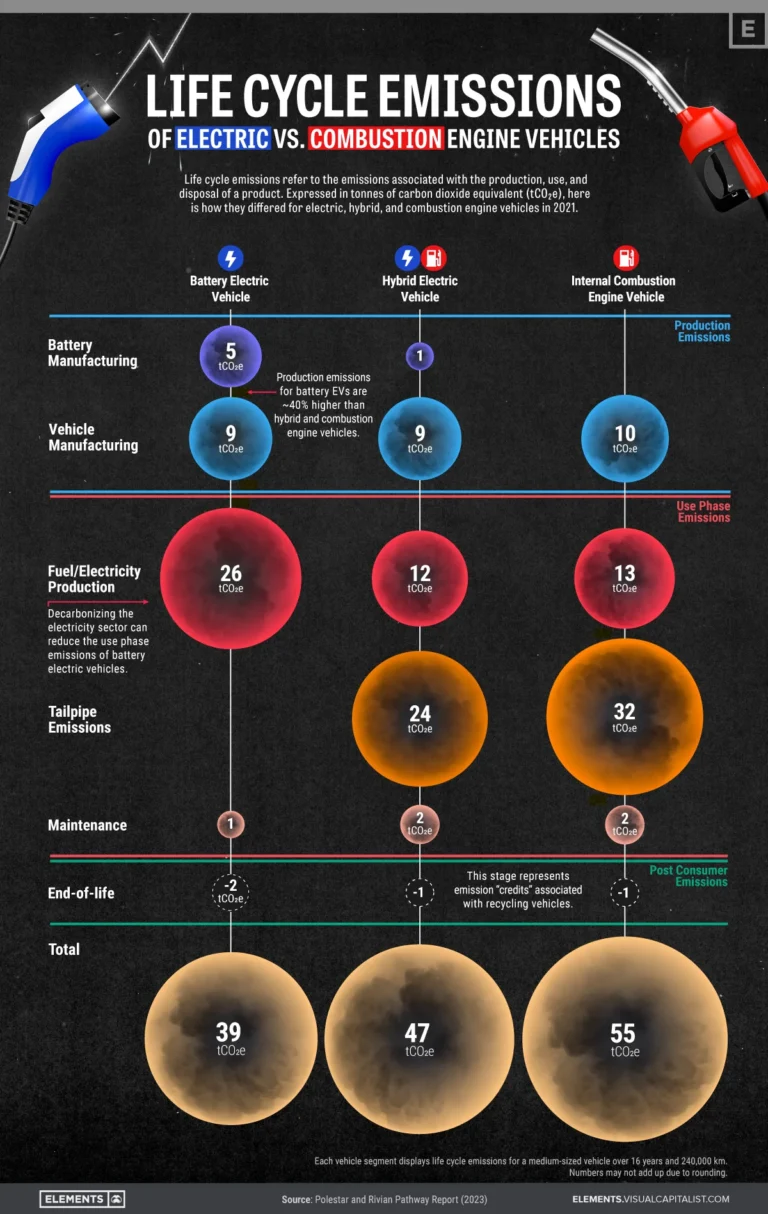

EV Life Cycle Emissions

When people think about car emissions, most think about tailpipe emissions – aka the ongoing smog that comes from the back of your car as you drive. These are considered “operational emissions” – and the major selling point of EVs is that they have none.

However, climate scientists look at the bigger picture, or the life cycle emissions associated with producing and distributing cars and their fuels.

Manufacturing Emissions

At the beginning of a car’s life cycle, there are the emissions from vehicle manufacturing, which we touched upon above. In addition to the carbon emissions from the manufacturing process, raw materials needed to make electric vehicle batteries, like cobalt and lithium, are acquired through difficult and hazardous mining operations. The massive amount of groundwater required for battery production also means making electric cars can use 50% more water than manufacturing traditional combustion vehicles.

As an example, manufacturing an average gas-powered sedan creates about six metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions, but manufacturing an electric vehicle of the same size creates more than 10 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions. As EVs become more popular, the problem is getting more attention, and even EV automakers are calling to decarbonize supply chains.

While manufacturing EVs produces more carbon emissions than internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, the EVs are cleaner over their lifetimes.

Operational Emissions

Electric cars produce no tailpipe emissions when they are used. No smog, no nitric oxide, nothing to make the air on the ground bad to breathe. Gas cars, of course, produce a lot of tailpipe emissions. In fact, they can produce 32 metric tons of carbon dioxide over a 16-year lifetime, while EVs produce none. The more you can use an electric car, the cleaner it becomes, when compared to a gas car.

Upstream Emissions

Whether you are powering an EV or a conventional car, the fuel production process yields carbon emissions. For gas cars, this means the emissions that come from drilling for gas and refining it. For EVs, upstream emissions are those associated with generating electricity from natural gas, coal or even renewable sources.

Non-renewable fuel still accounts for 80% of electricity production nationally, so producing electricity is not yet spotlessly clean, and globally, is still twice as dirty as refining gasoline. But, while producing gasoline will never be renewable or carbon-free, upstream emissions for electric vehicles can be reduced. Switching to renewable energy sources, like solar or wind power, can make electricity very clean, and the U.S. power system is ready for an upgrade. Regulators recently approved several reforms to speed up the connection of new, renewable power projects to the electric grid. (To learn more about upstream emissions where you live, check out the EPA’s Beyond Tailpipe Emissions Calculator.)

While EVs may be powered by electricity generated by fossil fuel, even coal, over the long term their carbon emissions are still far lower than a conventional car.

EV vs. Combustion Engine Emissions

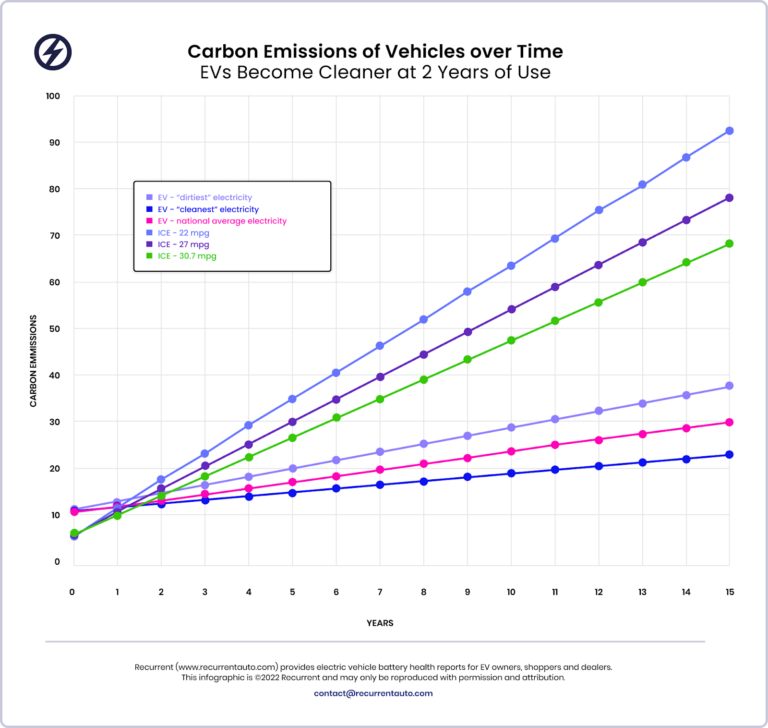

To accurately compare the impact of gas cars and electric vehicles on the environment, we need to take into account the complete life cycle of each car – from manufacturing, to use, to when the cars get taken off the road. The infographic above is one recent analysis.

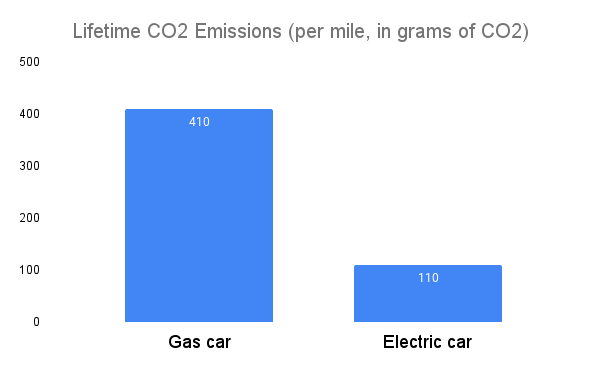

Here are some numbers from the US EPA.

Gasoline powered vehicles start with manufacturing emissions, and then release 8,887 grams of carbon dioxide in tailpipe emissions for every gallon of fuel burned. Electric vehicles produce zero tailpipe emissions, but do have associated upstream and manufacturing impact. So what does this look like over an average lifespan of a car?

Over the course of its life, a new gasoline car will produce an average of 410 grams of carbon dioxide per mile. A new electric car will produce only 110 grams.

Over the course of its life, a new gasoline car will produce an average of 410 grams of carbon dioxide per mile. A new electric car will produce only 110 grams.

Can EVs Ever Catch Up?

Since EV manufacturing creates more emissions than ICE manufacturing, but their operational emissions are lower – how long does it take for an electric vehicle to break even with a gas powered car? When are electric cars really “cleaner” than gas cars? Turns out it only 1.4 to 1.9 years.

It takes fewer than two years for an electric vehicle to catch up and surpass gas fueled cars when it comes to lifetime reduction in emissions. That’s regardless of where your electricity comes from or how good an internal combustion engine vehicle’s gas mileage.

Although no car is perfectly green, choosing the right vehicle can reduce your carbon footprint. The average American owns as many as nine cars over the course of their lifetime. If all nine are gas powered, they’ll add 693 metric tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. If you buy nine new electric cars, their lifetime carbon emissions will be 270 metric tons, or less than 40% of what would have been created if you’d chosen to buy new gas vehicles.

Plus, this calculation assumes that the electric grid doesn’t change, which we know it will.

Beyond Carbon

Carbon pollution isn’t the only concern regarding protecting the environment. A 2019 meta-analysis found that noise pollution from human activity should be considered a serious form of environmental change. Noise pollution hurts land and sea animals, and our health, as well. The World Health Organization strongly recommends reducing noise levels from road traffic to below 53 decibels during the day and 45 decibels at night. A busy street is about 75 to 85 decibels, loud enough that extended exposure can permanently damage hearing. Electric vehicles, on the other hand, are so quiet that federal law requires EVs to generate artificial sounds when at low speeds to ensure pedestrian safety.

EVs are also important for keeping the air in our local communities clean. Research shows more electric vehicles on the road improve air quality, regardless of how the electricity is generated. Many health conditions are worsened by ozone, particulate matter, and other pollutants, and the impacts of air pollution disproportionately affect minorities and disadvantaged communities. Choosing an EV means the air in your neighborhood, and your driveway, will be cleaner from day one.

The Green Cheat Code

The best way to reduce the environmental impact of a new car? Buy used! The battery and manufacturing processes are responsible for 35% of EV emissions. Buying a used EV reduces your carbon emissions to only the upstream emissions needed to power your vehicle. That’s about 1.3 metric tons annually, versus up to 5.8 metric tons for ICEVs.

The next thing to clean up is electricity generation. With improving technology, we hope to rely on a greener national electric grid in the near future. Depending on where you live, this may be a reality already. But, many EV drivers are also able to install home solar and charge their cars, for free, using the sun. Gas car drivers will never have access to clean energy like that.

The other critical step that we don’t touch upon in this article is battery recycling, which will reduce the carbon footprint of battery manufacturing – especially mining and refining critical minerals. Companies in the U.S. and abroad are already working on this problem, and governments are finding ways to financially incentivize battery reuse and recycling. Hopefully this effort picks up steam and is up and running soon.

Visit Recurrent to learn more about electric vehicle battery health.

This article is originally researched and written by the team at Recurrent.

Note on Calculations:

Assumptions for calculations above include EV with a 300mi range, vehicle lifetime of 173,151mi, for both gas and electric. Assumes car is driven 11,500mi yearly. Tailpipe emissions for gas vehicles multiplied by a factor of 1.25 to account for emissions from gasoline production/transportation.

Emissions calculations for EVs taken from the EPA’s Power Profiler. The “cleanest” energy scenario is the CAMX eGRID, which uses the highest percentage of solar power nationally, and the “dirtiest” energy is the NYLI eGRID, which uses the highest percentage of gas power. National average assumes EVs generate 110g/mi with the average national fuel mix, 70g/mi with the CAMX mix, and 160g/mi with the NYLI fuel mix.

AAA’s Recommendation: Whether you own an electric vehicle or a gas-powered car is up to you – and you should consider lots of factors in making that choice. No matter what type of vehicle you’re choosing, we recommend visiting a dealership, test driving one, and asking as many questions as possible to make an informed decision.